Palo Alto, 1966

We lived in an apartment complex in Palo Alto with a flat roof and globe swag lights that hung like full moons. The complex was u-shaped, and across the U lived a girl a few years older than me who played with me when she had no other options. Suddenly, her birthday was nigh, and it came to my attention that she was having a party, not because she invited me but because it somehow became known. Maybe I spotted cake sprinkles on the kitchen counter or a stack of invitations featuring unicorns prancing through stardust.

I did not yet know that one could not petition to be invited to a party, just as you can ask people to care about you. I didn’t know yet that we choose people instinctually. People are either a “yes” or a “no” for us. Rom-coms are about Nos becoming Yeses, and this is one of the reasons they are evil. They breed false hope.

So, I schemed and frankly begged to be invited. I asked her mother point blank if I could come. I knew it was wrong but couldn’t let her off the hook. She said it was a party for older girls. I argued that I was old for my age. I asked the girl. I asked my mom. Part of me did know there was something shameful in this cajoling. But my longing to attend this Shangri-La of a party with deeply frosted cake and unicorns and pin-the-tail trumped my shame. I had to be there.

And then suddenly word came down: I was in. I was incredulous and thought to pepper the girl’s mom with a repeated “Are you sure?” but I also didn’t want to push my luck.

And at the appointed hour on the long-awaited day, I ran across the U in my scratchy party dress and suddenly I was there in paradise, surrounded by cake and girls and balloons, and…I, I felt like I’d begged my way in. I felt unwanted.

And truly, that’s what I’d been after all along: To be wanted.

San Francisco, 1989

After an extended boyfriend drought, I finally had a boyfriend. I was beside myself with excitement because I really liked him. And because the relationship burst out of nowhere after the sort of dry spell in which it becomes impossible to comprehend how two people ever get together. How would it even start? Someone asks someone out? People meet where? Parties? Bars? At work? And they like each other and then one of them acts on it?

I was all Hot Chocolate’s “I beLIEVE in miracles! Where you from, you sexy thing?” I was saying a lot of stuff like, “My boyfriend and I…” and “I told my boyfriend….” I need to underscore that this was San Francisco in 1989. Really not an easy place to find a boyfriend. It didn’t help matters that I dragged an overstuffed cross-body bag full of books around the city along with my low self-esteem and heavy work schedule. Besides my job waiting tables, I tutored undergraduate students of color at San Francisco State where I was a grad student in English Literature, mostly students from Vietnam who were studying their way into a better life in America, which, of course, meant reading Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” and writing five-page essays on the ethical issues explored within. In between jobs I sat in cafes where I ate oversized muffins, drank lattes, and wrote papers on Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and French feminist theory—not exactly the fast track for meeting guys.

So, the boyfriend. We are going to call him Michael. The day Michael and I decided we were boyfriend and girlfriend happened to be the 4th of July and that night Michael mentioned his birthday was July 16th. I mentally logged the date and thought to myself, wow, that’s really coming up quick! I better figure this out! I’d waited so long for someone to love that I was completely prepared to lavish. I just needed a plan.

“I’m not sure if I should go with chocolate or something surprising like carrot,” I pondered out loud a few days later, vaguely addressing my inquiry to Maggie, headwaitress at the San Remo, the Italian restaurant where I waitressed four nights a week. “You know, for the cake?”

If I searched the earth, I could not be parsing through this cake decision with someone less sympathetic to this particular question than Maggie. I was twenty-seven and Maggie thirty-six. She resented the hell out of the nine years of youth I had on her, despite my dearth of confidence in my desirability. Maggie saw me as one of the young things who sashayed through the restaurant without a care while she toiled as a doomed spinster destined for an eternity of thankless servitude. In cutlery-napkin-rolling time conversations, she had a glib answer to every life question, although these answers never seemed to get she herself anywhere. Even though she ostensibly had a lot going for her—plans for becoming a therapist, her own condo in the East Bay, brains enough to incisively cut you down to size—her life was relentlessly empty. Telling Maggie plans of love was like telling Ebenezer Scrooge the itinerary for an upcoming shopping junket.

“Maybe a chocolate cake with a mocha frosting?” I suggested, fascinated by my choices, feeling certain that everyone in the world must be rooting for me to make it the ball in my pumpkin and home again before the clock strikes midnight.

“Woah!” Maggie said, one hand of red acrylic nails forming a fatigued stop sign and the other resting on an aproned hip. “Hold up there, girl. Getting a bit ahead of ourselves, aren’t we? Aren’t you afraid of scaring him away?”

“What? No! We’re totally into each other. What do you mean?”

“It’s too much. It’s like ‘Love me! Love me!’ Don’t you think?”

“No. I think it’s nice.” I answered, defensiveness thick in every word.

“When’s your birthday?” She asked, scooping an ice cube out of ice machine and popping it into her mouth. She was the mechanic. All she needed was for me to pop the hood.

“August third.”

She cocked her head and raised an eyebrow and said evenly, “Yeah. Too bad. He’s in the power seat.”

“There is no power seat!”

“Right. Let’s see what you say about that on August 4th,” she said cooly. “Look, can’t you see it’s a set up? You have to go first. Whatever you do sets up the game. You move any piece and he’ll have your queen,” and with that she spun on a heel toward the table of blue-haired regulars who’d just been seated in her section, her sour expression dissolving into her game face. On an average night, she made twice as much as me in tips.

“I believe in miracles!” evaporated. I wanted Maggie to be wrong, wrong, wrong. We weren’t game players! I argued to myself, but insecurity crept into my thoughts. Was I begging him to love me? Could I scare him away simply by doing what instinct told me to do—to make his birthday nice? I wanted to take all my energy and funnel it into creating something beautiful. I wanted to sacrifice an afternoon to baking and have it feel like no sacrifice at all. I wanted, in sum, to love and be loved. Yet, it was hard not to be convinced by Maggie. Doubt eroded my confidence. I halved my celebration plans, but still made a poppyseed cake frosted with vanilla buttercream.

Not long after his birthday, Michael began to worry aloud to me that he would end the relationship abruptly, as he had with his past relationships. Despite the heart-pounding queasiness I felt during these bouts of speculation, I refused to see them as a bad sign. I also refused to see it as a bad sign that during these conversations, I did not ask for reassurance but instead helped parse through his fear that he might bolt and reassured him that his awareness of a pattern was a sign that he was ready to change. Thanks, therapy! Yet, worry began to settle in on a molecular level, and whatever power I had in the relationship was subtly and incrementally shifting to him. Scales tipped.

On my birthday, he gave me a beautiful blouse and a small photo album of photos of him alone in various stages of life. I both wanted the album and was repelled by it. I laughed a little too loud when he joked, “I guess it seems a tad narcissistic to give someone pictures of yourself!” Oh, not at all. Don’t be silly!

By September I was watching for signs of his pleasure and displeasure and rushing to my answering machine as soon as I got home to see if he’d called. As I fell deeper into the relationship, I imagined that he with his underground zine and college radio station aesthetic was cooler than me. In conversation, I was too eager to impress, dropping references to Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida. Somehow, he’d gotten the power. It was no mystery really; by questioning the fate of the relationship, he’d sealed the deal. He’d gotten the power seat. Yes, there was a power seat.

One day in the middle of October, I was sitting at my desk finishing a paper on Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own when a rumble rippled through the floor. For a second or two, I thought it was the N Judah rounding the corner onto Ninth. But then a cobalt vase of Markos’ rolled onto its side and a fissure snaked its way through the white plaster of my wall. Dishes leapt from the drying rack and shattered onto the black and white tile. I heard the two boys run out of their apartment down the hall and yelling in Spanish near my door. By the time I made it out there the youngest one crying. “Come with me,” I said in English and grabbed his hand and we ran together with his brother down the five flights of stairs and out of the building into the street. The shaking had ended, but the fear that it could start again remained.

In front of my building a crowd gathered, exchanging stories. I stood with the boys there until their dad rushed up, thanked me, and led the boys away. A man with a Watchman TV joined our sidewalk cluster. I glimpsed over his shoulder and saw footage of a fire in the Marina district. I wondered if Michael was okay. He worked down the Peninsula, and the earthquake happened at 5:17pm, twenty minutes after quitting time. We had a plan to get together later. Was he driving home? Had the freeways been impacted? Was he alive?

My neighbor friend, Rachel, walked up just then, and we started wandering the streets together looking for a working pay phone. It was a strangely sunny and glorious day. The sun beat down on the sidewalk where acquaintances rushed to comfort each other. As we walked, Rachel talked about how worried her parents must be. But my one real thought was of Michael. In that moment, I didn’t really care what my mom and my stepfather were thinking (Did they even know?). I wanted to call Michael, and this was pretty much my only thought as firetrucks blared by us and we walked past a brick apartment building reduced to rubble. Finally, we found a payphone. I called home at Rachel’s insistence. My parents had, in fact, seen the earthquake on the news and were very worried. Over fifty people were dead, and my mom said the Golden Gate had collapsed. I rolled my eyes.

“The Golden Gate has not collapsed,” I said, irritated.

“Okay,” my mom said, “another bridge then.”

The Bay Bridge? Okay, fine, but where’s Michael? I called his place and just let it ring and ring. Most of the residential lines were down, we’d heard from people on the street. With nothing left to do, Rachel and I returned to our building. An hour later we sat talking in my apartment with the door open (because somehow that felt safer) when Michael’s face rounded the corner. Relief rushed through me, followed by a warm sense of security. He’d come for me! We were really together now.

Michael and I quickly decided to stay at his place because he lived in a one-story house, which seemed a far safer choice than my five-story building. We wondered if night would bring more shaking. As I turned to say goodbye to Rachel, I realized that she had no one coming to stay with her or take her away, something I hadn’t even considered. I saw in her face that I wasn’t quite the friend she’d hoped I’d be.

“Do you want me to stay here? I could?” I asked, knowing that the damage was already done.

“No, I’ll be okay,” she said.

“Okay, I’ll try calling you in the morning. Maybe the phones will be working again by then,” I said and gave her a hug, knowing that a better friend would stay put. Michael had his roommates after all.

Despite the disaster all around us, I felt a coziness as we drove back to his house. People had died. The Marina was burning. The Bay Bridge had (partially) collapsed. I’d left my friend to fend for herself. But my boyfriend had come to get me! Now we can huddle together and exchange words of love and perhaps even make out relentlessly the way Hawkeye and Hot Lips Houlihan did in that one episode of M.A.S.H. when gunfire exploded into the night all around them as they huddled together in a deserted hut.

My secret plans for foxhole rapture screeched to a halt when we arrived at his place in Noe Valley. Conducting an inventory of the damage to the house with jangled roommates was not romantic at all. One of his roommates was worried about a coworker who possibly might be stuck in their office building downtown. When he’d left there two hours ago, he hadn’t noticed whether she’d left their building safely or not. He’d tried calling her house, but there was no answer. All the phones are down, I offered. Yes, he said, but he was still concerned.

After much discussion, Michael and this roommate decided they would walk downtown searching for the coworker. Did I want to come with them or wait there alone? I opted to wait there, not anticipating the bleakness of the hours that lay ahead of me, lying in Michael’s bedroom with no electricity waiting for him to return. Who was this person he was “rescuing” and why were they so sure she needed their help? These were questions I couldn’t answer, although I spent hours trying.

Finally, he returned at 4am. The room was dark when he climbed into bed beside me. I thought I hadn’t slept at all, but I must’ve because now I was groggy. We lay on our sides facing each other. Light from a streetlamp illuminated the top of his head and a corner of his pillow, but his face was shadowed. He told a long story about walking downtown through streets of shattered glass, about arriving at this office and finally getting her on the phone and finding out she’d left the building hours earlier and walked safely home.

I made reassuring noises as I listened but thought to myself: You wanted to be a savior to some woman you’d never met who didn’t even need saving. You’d rather rush off to save a stranger than stay with a real girlfriend who needed reassurance. I thought about the hour after he’d left, how I’d worried that I might die or he might, but mostly I worried that my boyfriend would never love me. I wondered what makes love start. I shared none of this with him though. I didn’t want to be needy, to be the one who needed more love than would be given, the one who rushed in to bake a cake too soon.

A month later I headed my usual route to work, but then realized my shift didn’t start for another hour so jumped off the Powell Street cable car a stop early to wander around Washington Square. I spotted an antique shop and decided to go in.

“What are you looking for?” said the woman with long tousled hair perched on a stool behind the glass case stuffed with imported silver jewelry. Silver bracelets laced up both her arms, a loose weave black sweater bunched up above her elbows. Her eyes were lined with navy blue. I was used to living in a city of people cooler than myself by then.

“Just browsing. A Christmas present for my boyfriend maybe.”

“That’s nice,” she said, flatly. “Wish I could say the same. I’m mid-breakup myself. Not even mid. Just the shitty part after, you know?”

“Oh, yeah, know it well,” I said. I looked at her. We were both heading into our late twenties: Too young to be married—at least in San Francisco—and yet tiring quickly of the short-lived relationships of the twentysomethings. I got the feeling looking at her, I was looking at my future. “I’m sorry,” I said because I was.

“It was one of those things where you see that the person is really not there for you,” she said. “After the earthquake, I saw who he was and I was like no, I can’t. I can’t do another round of this.”

My heart dropped a bit with her words “I can’t.” I wondered what it was that I couldn’t do. Where was my limit? What would I not do another round of? It seemed like I was a long way from finding out.

Thanksgiving weekend I blurted out that I loved him. He didn’t reply until New Year’s. He told me then that he loved me too but then never mentioned that love again. We stumbled along until May—seeing each other slightly less often with each passing week—when I finally said, “I think you want to break up with me.” Not even “I want to break up with you.” Even in this moment of misery, I was thinking more about his feelings than my own.

The relationship broke right along the very fault line Peggy had zeroed in on the summer before, my desire for more pushing him away. Peggy—and pretty much all the jaded people in the world—are, in fact, right most of the time. But it’s not exactly a hard call. Every relationship you’re in is going to be wrong and will end in a breakup except for the one that lasts. The jaded can spot—because they want to see it—your fatal flaw, your neediness, your coldness, your fear of intimacy, your what have you. But whatever preventative measure they suggest you take to curb your flaw, it’s only going to slow down the eventual breakdown. Because no matter how you act, you still are that person. Just because you act like you’re not controlling or compulsive or desperate for love for a few months, doesn’t mean you’re not controlling or compulsive or desperate. The truth—the very you of you—comes out. No matter how much I might dial it back, I was still the person who wanted to be deeply ensconced in a relationship I could give my whole heart to and Michael would still be the person who needed to pull away from such eagerness.

In the weeks after we broke up, I turned my attention to my master’s thesis, which in the last anxious days of the relationship, I’d pretty much set aside after turning in the first eight pages to my thesis advisor. The thesis was supposed to be 100 pages, so 92 pages stood between me and graduating and looking for work other than tutoring and waitressing. But I’d finished all my classes and I had no boyfriend so other than my 27 hours a week at the San Remo, I had nothing but time.

The thesis topic seemed laughably arcane at an urban American university, but I’d already chosen it, had it approved, and done much of the research. And picking up the thesis again, I saw that with it I’d chosen myself: The focus was something I’d titled, “The Canadian Cottage Novel,” a study of three novels by Canadian women whose protagonist left the world behind for a life of agency in isolation. Over the next few months, I sat alone in the world of Margaret Atwood, Audrey Thomas, and Margaret Laurence. Surfacing was the title of the Atwood novel, and with it I did surface. I underlined, stacked notecards in meaningful piles across my apartment floor, and typed. These writers were subversive, I said. They refused to play, I argued. They took back their power, I wrote.

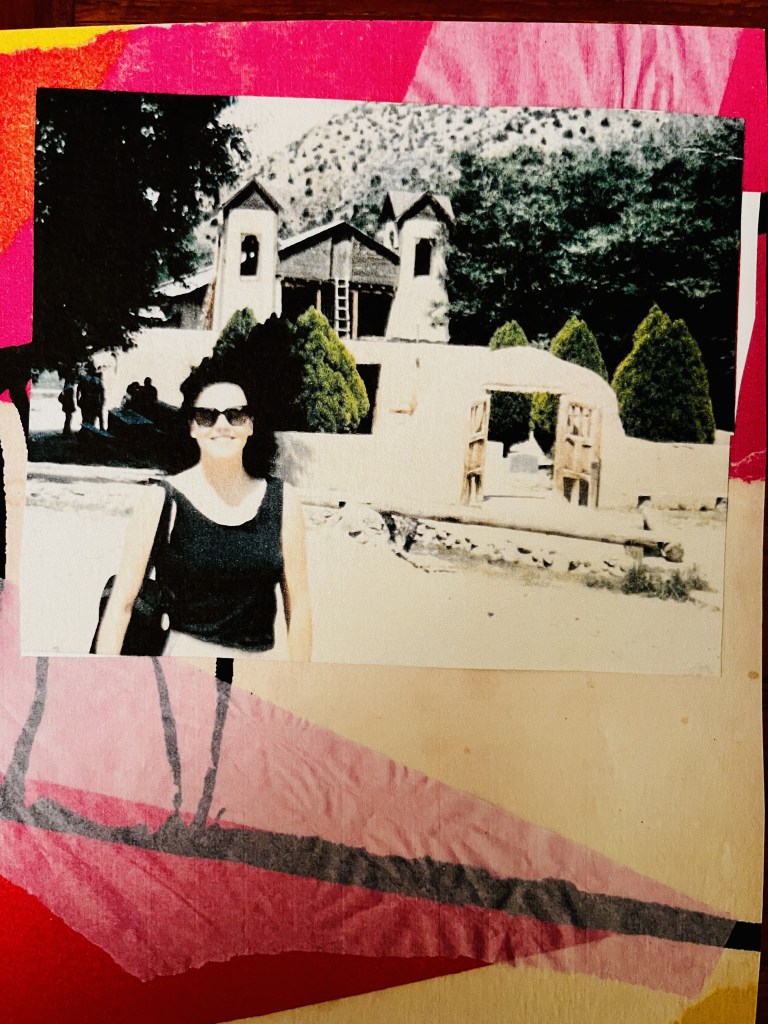

Vancouver, 1972

I once cracked open a fortune cookie and found this: “Always give the stepchild the extra piece of cake,” which reminded me of my stepfather, who took me on as one of his own, who I began calling “my dad” days after he and my mother married—even with him I had rushed in.

They married the August I turned ten, a union that changed my life forever, one that moved me from California to Canada, that ensconced me in fairly large and close-knit Irish family that had a sense of ritual and order that was lacking in my fractured family. One of those rituals was Grandma Mehaffey’s stunningly perfect layer cake as the centerpiece of birthday celebrations. When my new cousin’s cake emerged from the kitchen one late July afternoon in 1972, my being lit up with desire for this pale pink cake to be my own. After she blew out the candles, the first incision revealed two pale pink layers of cake sandwiching a white one, the three perfect layers separated by a thick layer of the butter cream frosting the pale pink of cherry blossoms.

It wasn’t enough to eat this cake. I wanted one exactly like it baked for my birthday the very next week. But I couldn’t be certain that it would happen. My cousin, after all, was a biological granddaughter. I was a new-to-the-scene step-granddaughter, if there even is such a thing.

I knew that I would need to ask for the cake. Without the ask there would be no cake. The request could be denied. I knew that Grandma Mehaffey disapproved of my stepfather’s third marriage, of my mother—a bleached blonde who was also on her third marriage—and by extension her disapproval of the marriage and my mother and her “bottle blonde” hair was also a disapproval of me. But I asked. I mustered courage I didn’t possess to make the request. That’s how much I wanted the cake.

“I don’t see why not,” she said, almost breezily. She, an old woman from Belfast who said nothing breezily, who could rule the world with the lift of a single eyebrow, who could pronounce a too weak cup of tea “undrinkable” and the kettle would be promptly reheated.

I took in the breeze of her response. I understood instantly and with my entire body that the request had shifted her opinion of me. Inexplicably, she wanted to make the cake. Years later when I reread The Little Prince, the words of the fox struck me to my core, “But if you tame me, then we shall need each other.” We grow to love the people we take care of. I’d given her the chance to take care of me, to love me.

A week later my pale pink cake burst from her kitchen ablaze with eleven candles. It was a cake made from scratch just for me. There had been sifting of dry ingredients and creaming of butter and sugar. There had been oven preheating and the cooling of steamy cakes on wire racks. There had been an afternoon of baking. There had been sacrifice.

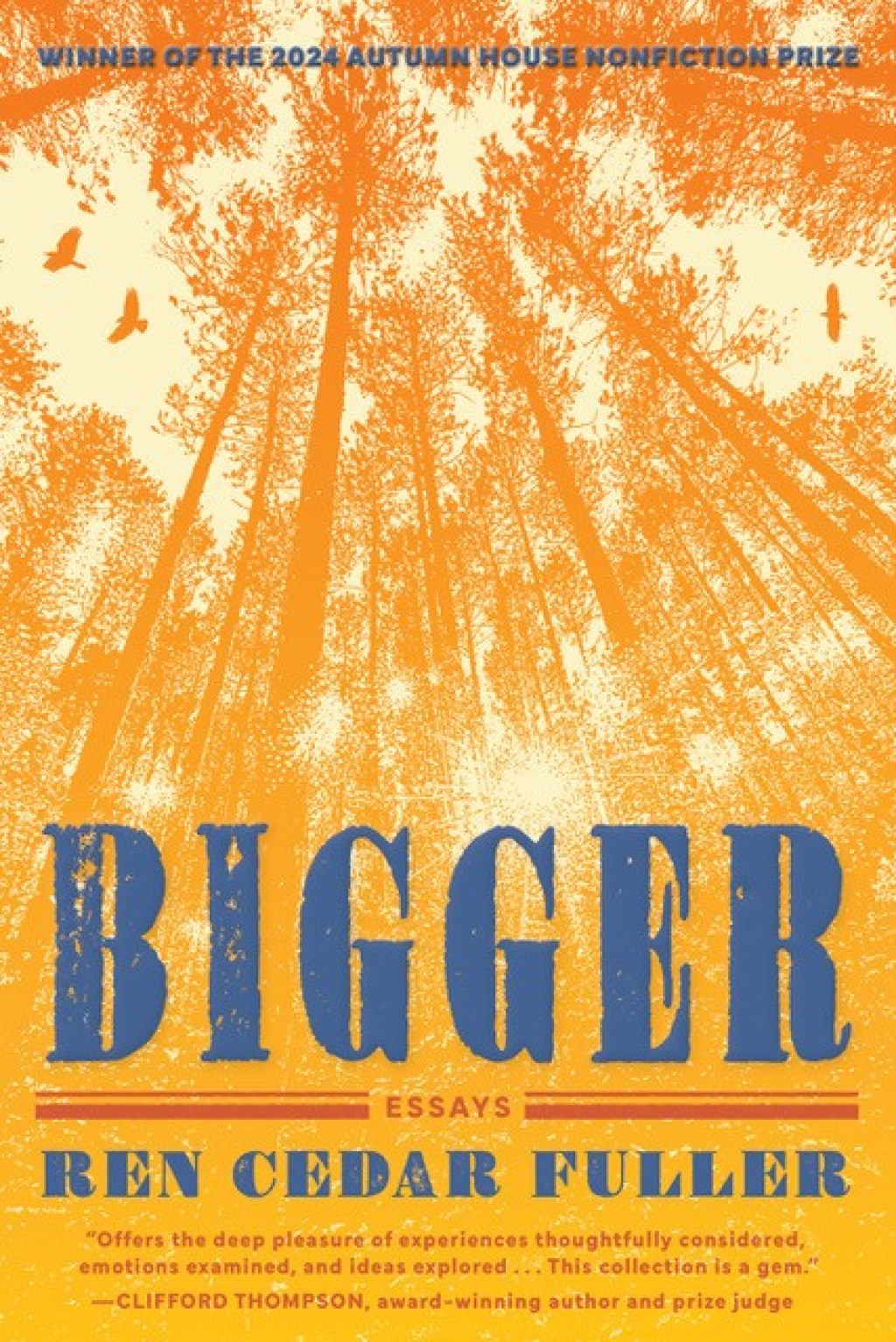

Click on thumbnails below to read more essays from My American ’80s:

Leave a reply to Pie – Writing Is My Drink Cancel reply